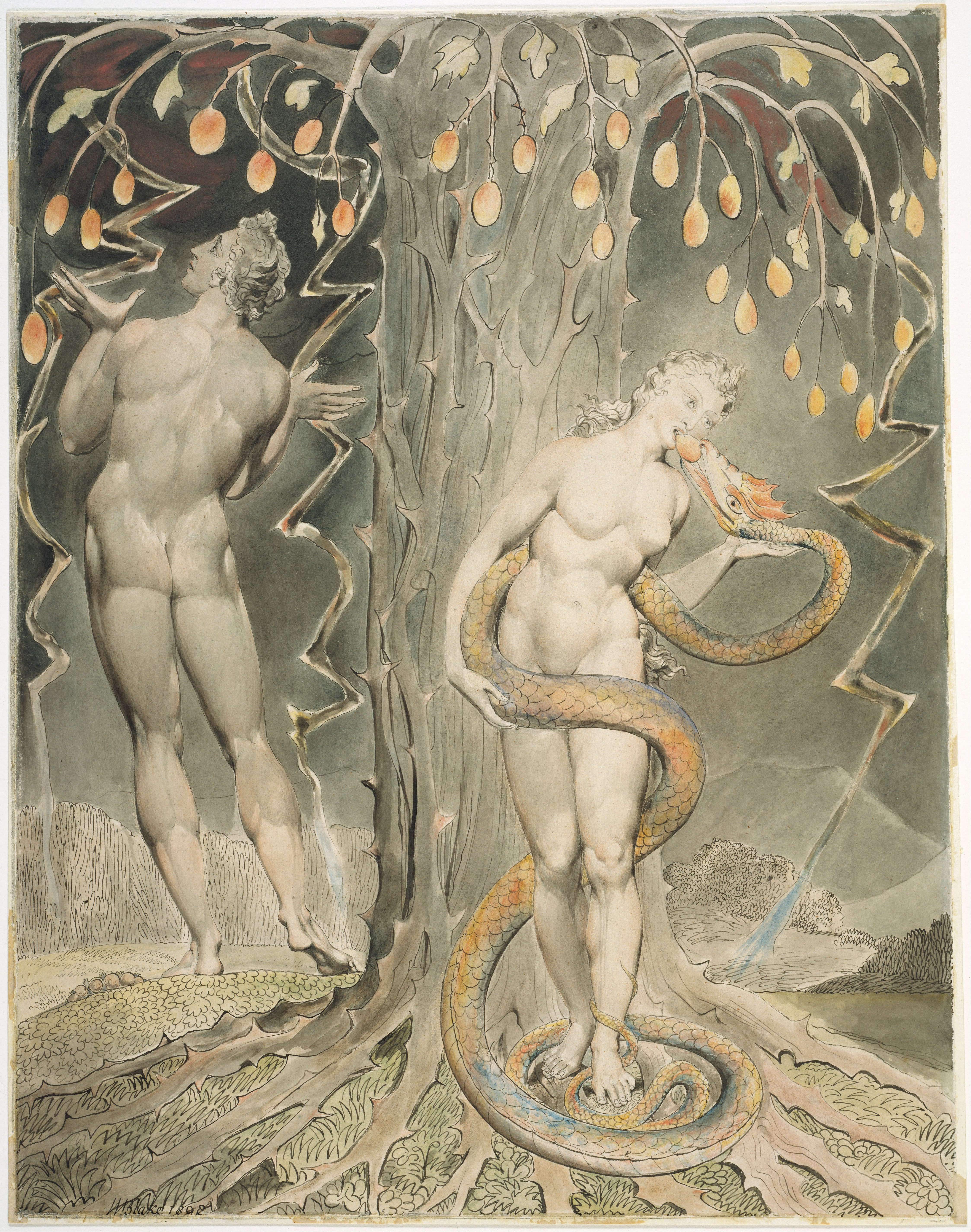

John Milton’s fame rests primarily on Paradise Lost, his Biblical epic on the war in heaven between God and Satan and the fall Adam and Eve, which exercised an enormous influence on subsequent generations of British (as well as American) writers. However, Milton’s works were also very much the product of their time. Milton lived through one of the most revolutionary periods of English history, the Civil War (1642-51), which led to the unprecedented execution of King Charles I for treason against his own people and the subsequent establishment of an English republic. More than a mere observer, Milton was an active participant in the political developments of his day. He passionately wrote against press censorship and religious persecution, he published treatises that justified the execution of a King who turns tyrant, and he served as secretary of foreign tongues in the administration of the newly established Commonwealth of England under Oliver Cromwell. Not least, Milton also gained notoriety for his divorce tracts, in which he (unhappily married himself) advocated for the legitimacy of divorce on the grounds of mutual incompatibility. When the monarchy was restored in 1660, Milton was imprisoned temporarily and was lucky to survive the regime change. As one contemporary put it, it would be ‘a strange omission if he was forgot, and an odd strain of clemency.’ Disappointed, out of a job, and completely blind by now, he turned to his Biblical epic Paradise Lost. While Milton’s reworking of the Christian creation myth in Genesis may seem like a form of literary escapism at first glance, contemporaries suspected that it was also an allegory of the loss of England’s political liberties. Indeed, in Milton’s time, there were no clear-cut boundaries between literature and propaganda or between aesthetics and politics. We will therefore consider John Milton as a revolutionary writer in various ways: as literary innovator, but also as a politically engaged writer, who championed principles of liberty that have become foundational to modern conceptions of democracy and rule of law.

This lecture will introduce students to Milton’s time and offer a survey of the whole breadth of his writings: his epics and shorter poems, his drama, but also his non-fictional writings, such as his classic defence of freedom of speech and press, Areopagitica (1644). While excerpts from Paradise Lost will be at the core of this lecture, these will be paired with Milton’s regicide and divorce tracts, for instance, to convey a sense of the contemporary political echoes in Satan’s rebellion against God or questions concerning gender and marriage in Milton’s portrayal of Adam and Eve. Finally, we will also discuss Milton’s more general significance in literary history. We will do so by (selectively) tracing his reception with a particular focus on the Romantics, who appreciated Milton as a pioneer of the aesthetic of the sublime and revaluated Satan as an unjustly maligned rebel figure, as exemplified by the creature in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, who is an avid reader of Paradise Lost and identifies with Satan because he feels equally unloved by his creator.

Note for MA students: this lecture can be taken as part of English Literature I (1500-1780) as well as English Literature II (1780-present). Students are also encouraged to combine this lecture with Prof. Austenfeld’s MA seminar on Milton in America, which will offer a more comprehensive picture of Milton’s afterlives.

- Teacher: Honor Jackson

- Teacher: Kilian Markus Schindler